MENU

The Electronic Scholarly Publishing Project: Providing world-wide, free access to classic scientific papers and other scholarly materials, since 1993.

More About: ESP | OUR CONTENT | THIS WEBSITE | WHAT'S NEW | WHAT'S HOT

ESP Library: Digital Books 14 Jul 2025 Updated:

Digital Books

ESP presents a browsable collection of digital books on a variety of topics. All of these books are available in their entirety on this website.

Digital Books

Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation.

London: John Churchill.

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 390-page original first edition.

In 1859, many had already begun to think deeply about the meaning and origin of creation. Fifteen years before the Origin, Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation appeared, published anonymously. In one sense, the book is hopelessly dated, and amateurish to boot. In another, the book is incredibly modern - an effort, in the author's own words, "to connect the natural sciences into a history of creation."

At one point, the author (revealed in the 12th edition to be Robert Chambers) uses the example of Charles Babbage's calculating engine (the first computer) to show how apparently miraculous changes might occur as the result of subtle changes in an underlying governing system.

NOTE: This is an electronic FACSIMILE of the original work. The PDF files contain images of the original pages. The files are large and will download slowly. It is probably best to download the files to disk for later viewing and printing. When printed, these files give output equivalent to good quality Xerox copies of the original.

This is a full-text PDF version of the entire book.

Aristotle’s On the Generation of Animals (in Latin, De Generatione Animalium) was produced in the latter part of the fourth century B.C., exact date unknown. This book is the second recorded work on embryology as a subject of philosophy, being preceded by contributions in the Hippocratic corpus by about a century. It was, however, the first work to provide a comprehensive theory of how generation works and an exhaustive explanation of how reproduction works in a variety of different animals. As such, De Generatione was the first scientific work on embryology. Its influence on embryologists, naturalists, and philosophers in later years was profound. A brief overview of the general theory expounded in De Generatione requires an explanation of Aristotle’s philosophy. The Aristotelian approach to philosophy is teleological, and involves analyzing the purpose of things, or the cause for their existence. These causes are split into four different types: final cause, formal cause, material cause, and efficient cause. The final cause is what a thing exists for, or its ultimate purpose. The formal cause is the definition of a thing’s essence or existence, and Aristotle states that in generation, the formal cause and the final cause are similar to each other, and can be thought of as the goal of creating a new individual of the species. The material cause is the stuff a thing is made of, which in Aristotle’s theory is the female menstrual blood. The efficient cause is the “mover” or what causes the thing’s existence, and for reproduction Aristotle designates the male semen as the efficient cause. Thus, while the mother’s body contains all the material necessary for creating her offspring, she requires the father’s semen to start and guide the process.

This is a full-text PDF version of the entire book.

Any collection of critical works in the history of biology must include works by Aristotle, as Aristotle was, essentially, the world's first biologist (if biologist is defined as one who conducts a scientific study of life). Although some earlier writers (e.g., Hippocrates) touched upon the human body and its health, no prior writer attempted a general consideration of living things. Aristotle held the study living things, especially animals, to be a critical foundation for the understanding of nature. No similarly broad attempt to understand biology occurred until the 16th century.

Here, in On the Parts of Animals, Aristotle provides a study in animal anatomy and physiology; it aims to provide a scientific understanding of the parts (organs, tissues, fluids, etc.) of animals.

This is a full-text PDF version of the entire book.

Any collection of critical works in the history of biology must include works by Aristotle. Here, in The History of Animals, Aristotle provides a discussion of the diversity of life, with considerable attention to reproduction and heredity.

In The History Aristotle frames his text by explaining that he is investigating the what (the existing facts about animals) prior to establishing the why (the causes of these characteristics). The book is thus an attempt to apply philosophy to part of the natural world. Throughout the work, Aristotle seeks to identify differences, both between individuals and between groups. A group is established when it is seen that all members have the same set of distinguishing features; for example, that all birds have feathers, wings, and beaks. This relationship between the birds and their features is recognized as a universal. The History of Animals contains many accurate eye-witness observations, in particular of the marine biology around the island of Lesbos, such as that the octopus had colour-changing abilities and a sperm-transferring tentacle, that the young of a dogfish grow inside their mother's body, or that the male of a river catfish guards the eggs after the female has left. Some of these were long considered fanciful before being rediscovered in the nineteenth century. Aristotle has been accused of making errors, but some are due to misinterpretation of his text, and others may have been based on genuine observation. He did however make somewhat uncritical use of evidence from other people, such as travellers and beekeepers. The History of Animals had a powerful influence on zoology for some two thousand years. It continued to be a primary source of knowledge until in the sixteenth century zoologists including Conrad Gessner, all influenced by Aristotle, wrote their own studies of the subject.

See also WIKIPEDIA: History of Animals

This is a full-text PDF version of the entire book.

Francis Bacon was a contemporary of Queen Elizabeth I and Shakespeare. Bacon's philosophy emphasized the belief that people are the servants and interpreters of nature, that truth is not derived from authority, and that knowledge is the fruit of experience. Bacon is generally credited with having contributed to developing the logic of inductive reasoning, and thus to developing the scientific method.

Loren Eiseley (in The Man Who Saw Through Time) remarks that Bacon: "...more fully than any man of his time, entertained the idea of the universe as a problem to be solved, examined, meditated upon, rather than as an eternally fixed stage, upon which man walked."

Bacon saw himself as the inventor of a method which would kindle a light in nature - "a light that would eventually disclose and bring into sight all that is most hidden and secret in the universe." This method involved the collection of data, their judicious interpretation, the carrying out of experiments, thus to learn the secrets of nature by organized observation of its regularities.

Materials for the Study of Variation.

London: Macmillan and Company.

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 598-page original first edition.

William Bateson was the first English-speaking scientist to recognize the significance of Mendel's work. Before the rediscovery of Mendel's work in 1900, Bateson had been active in studying morphology, with a special interest in discontinuous variation as it might apply to the origin of species.

In this book Bateson summarizes his observations on discontinuous variation. His concern for this kind of variation probably contributed greatly to the quickness with which he grasped the significance of Mendel's work.

NOTE: This is an electronic FACSIMILE of the original work. The PDF files contain images of the original pages. The files are large and will download slowly. It is probably best to download the files to disk for later viewing and printing. When printed, these files give output equivalent to good quality Xerox copies of the original.

Mendel's Principles of Heredity: A Defence.

London: Cambridge University Press.

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 212-page original first edition.

William Bateson was the first English-speaking scientist to recognize the significance of Mendel's work. In an 1899 paper, he had anticipated the sort of experimental design that Mendel used, and in 1900, shortly after Mendel's rediscovery, he published another paper in which he summarized Mendel's work in English, declaring it to be "a new principle of the highest importance."

In the present work, Bateson offers a book-length presentation of Mendel's approach to genetic research, including the first English translation of both Mendel's work on peas and his later work on Hieracium. The book is subtitled A Defence because the Mendelian approach to genetics was initially strongly resisted by the biometrician school, which based their thinking on Galton's ancestral law of heredity.

NOTE: This is an electronic FACSIMILE of the original work. The PDF files contain images of the original pages. The files are large and will download slowly. It is probably best to download the files to disk for later viewing and printing. When printed, these files give output equivalent to good quality Xerox copies of the original.

The Methods and Scope of Genetics.

London: Cambridge University Press.

This is a newly typeset full-text version of the entire 49-page original first edition.

This short book is a copy of the Inaugural Address, given by Bateson upon the creation of the Professorship of Biology at Cambridge. In his introduction, Bateson notes:

The Professorship of Biology was founded in 1908 for a period of five years partly by the generosity of an anonymous benefactor, and partly by the University of Cambridge. The object of the endowment was the promotion of inquiries into the physiology of Heredity and Variation, a study now spoken of as Genetics.

It is now recognized that the progress of such inquiries will chiefly be accomplished by the application of experimental methods, especially those which Mendel's discovery has suggested. The purpose of this inaugural lecture is to describe the outlook over this field of research in a manner intelligible to students of other parts of knowledge.

Here then is a view of how one of the very first practitioners of genetics conceived of the "Methods and Scope of Genetics".

The Law of Heredity, Second Edition.

Baltimore and New York: John Murphy & Co., Publishers.

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 336-page original first edition.

It is often thought that, besides Mendel, little work on heredity occurred during the 19th Century. This is far from true. Darwin's Origin of Species placed the study of inherited variation at the center of biological thought. As this work by Brooks attests, considerable effort was made to understand heredity, especially as it related to natural selection.

Although the details of Brooks' analysis are now outdated, the book provides general insights into late-nineteenth Century thinking on heredity. Since Brooks was one of T. H. Morgan's instructors when Morgan was a student at Johns Hopkins, the book also provides insights into the specific instruction on heredity that was presented to the man who became the first recipient of a Nobel Prize for work on genetics.

NOTE: This is an electronic FACSIMILE of the original work. The PDF files contain images of the original pages. The files are large and will download slowly. It is probably best to download the files to disk for later viewing and printing. When printed, these files give output equivalent to good quality Xerox copies of the original.

Heredity in Relation to Evolution and Animal Breeding.

New York: D. Appleton and Company

This is an image facsimile version of the entire 184-page original edition.

The Voyage of the Beagle, Second Edition.

London: John Murray.

This is a full-text, newly typeset, PDF version of the entire book.

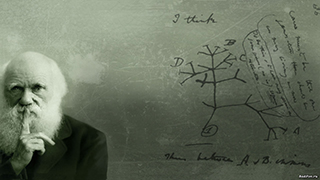

For five years, from 1831-1836, Charles Darwin served as the official naturalist aboard the HMS Beagle as it visited exotic locations around the world. During this voyage, Darwin first came to wonder about the mechanisms driving the origin of species. This book chronicles the voyage and documents his early thinking.

London: John Murray, Albemarle Street.

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 502-page original first edition.

This is the book that changed the world and defined modern biology. By making mechanisms of heritable variation central to the biggest issue in all of biology, Darwin initiated the genetics revolution.

The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, Second Edition, Revised (two volumes).

New York: D. Appleton & Co.

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 473-page volume I and the entire 495-page volume II of the original work.

Although Darwin's theories regarding the origin of species through natural selection required that some mechanism of heredity exist, no such mechanism was known when the Origin was written. After the Origin appeared, Darwin turned his attention to the mechanism(s) of heredity, resulting in his subsequent two-volume The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication.

In volume I, Darwin summarized what was known about inheritance in a variety of domesticated species and concluded with a chapter, Inheritance, that begins his general summary of the mechanisms of inheritance. He continued this summary in volume II, which also offers Darwin's own theory of inheritance in Chapter XXVII, Provisional Hypothesis of Pangenesis.

The notion of pangenesis dominated late nineteenth-century thinking about inheritance. Although ultimately seen to be simply wrong, it was very influential and a familiarity with its tenets is essential for anyone wishing to understand the intellectual climate at the time Mendel was rediscovered in 1900.

NOTE: This is an electronic FACSIMILE of the original work. The PDF files contain images of the original pages. The files are large and will download slowly. It is probably best to download the files to disk for later viewing and printing. When printed, these files give output equivalent to good quality Xerox copies of the original.

Heredity in the Light of Recent Research.

Cambridge: University Press

This is an image facsimile version of the entire 144-page original first edition.

London: J. M. Dent & Sons.

This is an image facsimile version of the entire 48-page original first edition.

This short book was based on a lecture given by Drinkwater as one of a series known as "Science Lectures for the People." The book provides insights into the general perception (as opposed to scholarly view) of genetics very early after the field had begun.

The book also contains some nice portraits of Mendel, Bateson, and Punnett.

London: Macmillan

This is an image facsimile version of the entire 260-page original first edition.

London: Macmillan

This is an image facsimile version of the entire 260-page original first edition.

Inborn Errors of Metabolism, Second Edition.

London: Henry Frowde and Hodder & Stoughton

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 216-page original book.

Less than two years after the rediscovery of Mendelism and just a few years after the word biochemistry was first coined, Garrod reported on alkaptonuria in humans and came to the conclusion that it was inherited as a Mendelian recessive and that the occurrence of mutations (sports in the word of the time) in metabolic function should be no more surprising than inherited variations in morphology.

In 1908, he summarized his thinking about "inborn errors of metabolism" (his term for what we would now think of as mutations in genes affecting metabolic function) in a book. An image facsimile of the second edition (1923) of that book is presented here.

Like Mendel's work, Garrod's insights were so far ahead of their time that his entire work on metabolic mutations was largely neglected, until later efforts to elucidate the physiological functioning of genes led to the Nobel-prize-winning one-gene, one-enzyme hypothesis.

Proceedings of the Sixth International Congress of Genetics, Vol. I.

Austin, Texas: Genetics Society of America

This is an image facsimile version of the entire 396-page original edition.

The Proceedings of the Sixth International Congress of Genetics, held in 1932, offers a glimpse into classical genetics at the height of its power and influence. Thomas Morgan, who had just received the first Nobel Prize ever awarded in genetics, served as president of the congress.

The participants list reads like a who's who of classical genetics: The three rediscovers of Mendel — Correns, de Vries, and von Tschermak — all attended the meeting. Morgan, Sturtevant, and Muller gave talks. Population genetics and the relationship of genetics to evolution was discussed by R. A. Fisher, J. B. S. Haldane, and Sewall Wright.

NOTE: According to the Treasurer's Report, the total cost of the meeting was $17,583.58. Correcting for the effects of inflation, that would be $323,442.89 in 2018.

Principles of Geology, Vols 1-3.

London: John Murray

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire three volumes.

These three volumes transformed the way people thought about the history of the earth. To understand Darwin's thinking, one must be familiar with Lyell's view of geology.

An Essay on the Principle of Population.

PDF typeset file: 948,754 bytes - 134 pages - no figures

This book was first published anonymously in 1798, but the author was soon identified as Thomas Robert Malthus. The book predicted a grim future, as population would increase geometrically, doubling every 25 years, but food production would only grow arithmetically, which would result in famine and starvation, unless births were controlled. While it was not the first book on population, it was revised for over 28 years and has been acknowledged as the most influential work of its era. Malthus's book fuelled debate about the size of the population in the Kingdom of Great Britain and contributed to the passing of the Census Act 1800. This Act enabled the holding of a national census in England, Wales and Scotland, starting in 1801 and continuing every ten years to the present. The book's 6th edition (1826) was independently cited as a key influence by both Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace in developing the theory of natural selection.

rb> This book had a significant influence on Darwin as he looked for mechanisms that might explain evolutionary change. The influence shows, with Chapter Three of Darwin's Origin of Species entitled "Struggle for Existence".

New York: Dix, Edwards, & Co.

This is a full-text newly typeset, PDF version of the entire book.

Included in this collection of short works by Herman Melville (author of Moby Dick) is "The Encantadas" — a description of the Galapagos Islands.

The Physical Basis of Heredity.

Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 305-page original book.

In this book, T. H. Morgan (who would later receive the first Nobel Prize for genetics research) describes the model of heredity developed at Columbia by Morgan and his students.

The foundations of genetics were laid down by Mendel, and these were brought to the world's attention when his work was rediscovered by Correns, de Vries, and von Tschermak in 1900. But the real establishment of genetics as a real science, with a known physical basis, did not occur until the work outlined in this book became generally known.

To understand the true conceptual underpinnings of classical genetics, one must read the publications from "The Fly Room" at Columbia.

The Theory of the Gene, Revised and Enlarged Edition.

New Haven: Yale University Press

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 358-page original book.

This book, by T. H. Morgan, summarizes the state of knowledge on classical genetics in the mid 1920's.

Although Mendelism had quickly been accepted as a good phenomenological explanation for the patterns seen in Mendelian crosses, until the work of Morgan's group, it was still possible to consider Mendelism to be a purely theoretical model of heredity. As Morgan's group first established the relationship of genes to chromosomes, then developed the first genetic map, and went on to describe a variety of interactions between chromosomes and Mendelian factors, the conclusions they offered became inescapable – genes are physical objects, carried on chromosomes in static locations.

Less than 15 years after Morgan first started working with fruit flies, the foundations for a theory of the gene had been worked out – largely by Morgan and students working in his laboratory.

The Mechanism of Mendelian Heredity.

New York: Henry Holt and Company

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 262-page original book.

This book, by T. H. Morgan and his students, is the first work to articulate a comprehensive, mechanistic model to explain Mendelian patterns of inheritance.

Although Mendelism had quickly been accepted as a good phenomenological explanation for the patterns seen in Mendelian crosses, until the work of Morgan's group, it was still possible to consider Mendelism to be a purely theoretical model of heredity. As Morgan's group first established the relationship of genes to chromosomes, then developed the first genetic map, and went on to describe a variety of interactions between chromosomes and Mendelian factors, the conclusions they offered became inescapable - genes are physical objects, carried on chromosomes in static locations.

Morgan's group made genes real and this book is the first full-length presentation of their findings. It revolutionized the study of heredity.

The Development of the Frog's Egg: An Introduction to Experimental Embryology.

New York: The Macmillan Company

PDF image facsimile file: 46,153,994 bytes - 204 pages - several figures

Thomas Hunt Morgan is best known for his work in genetics, for which he received the Nobel Prize in 1933. Morgan's first research interest, however, was in embryology. This short book on frog development is his first book.

From the Preface: The development of the frog's egg was first made known through the studies of Swammerdam, Spallanzani, Rusconi, and von Baer. Their work laid the basis for all later research. More recently the experiments of Pfluger and of Roux on this egg have turned the attention of embryologists to the study of development from an experimental standpoint. Owing to the ease with which the frog's egg can be obtained, and its tenacity of life in a confined space, as well as its suitability for experimental work, it is an admirable subject with which to begin the study of vertebrate development. In the following pages an attempt is made to bring together the most important results of studies of the development of the frog's egg. I have attempted to give a continuous account of the development, as far as that is possible, from the time when the egg is forming to the moment when the young tadpole issues from the jelly-membranes. Especial weight has been laid on the results of experimental work, in the belief that the evidence from this source is the most instructive for an interpretation of the development. The evidence from the study of the normal development has, however, not been neglected, and wherever it has been possible I have attempted to combine the results of experiment and of observation, with the hope of more fully elucidating the changes that take place. Occasionally departures have been made from the immediate subject in hand in order to consider the results of other work having a close bearing on the problem under discussion. I have done this in the hope of pointing out more definite conclusions than could be drawn from the evidence of the frog's egg alone.

Facts and Arguments for Darwin.

London: John Murray, Albemarle Street

Johann Friedrich Theodor Müller (March 31, 1821 – May 21, 1897), always known as Fritz, was a German biologist and physician who emigrated to southern Brazil, where he lived in and near the German community of Blumenau, Santa Catarina. There he studied the natural history of the Atlantic forest south of São Paulo, and was an early advocate of Darwinism. He lived in Brazil for the rest of his life. Müllerian mimicry is named after him.

Müller became a strong supporter of Darwin. He wrote Für Darwin in 1864, arguing that Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection was correct, and that Brazilian crustaceans and their larvae could be affected by adaptations at any growth stage. This was translated into English by W.S. Dallas as Facts and Arguments for Darwin in 1869 (Darwin sponsored the translation and publication). If Müller had a weakness it was that his writing was much less readable than that of Darwin or Wallace; both the German and English editions are hard reading indeed, which has limited the appreciation of this significant book.

The Mechanism of Crossing-over.

New York: The American Naturalist

This is an image facsimile version of the entire 86-page original edition.

Beginning 1910, T. H. Morgan and his students established the foundations of modern genetics by demonstrating that genes were real — not theoretical — entities.

This work is a collection of papers that represented the doctoral dissertation of one of those students - H. J. Muller.

Cambridge: Bowes and Bowes

PDF image facsimile file: 1,382,040 bytes - 71 pages - several figures

Reginald Punnett was born in 1875 in the town of Tonbridge in Kent, England. Attending Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, Punnett earned a bachelor's degree in zoology in 1898 and a master's degree in 1901. Between these degrees he worked as a demonstrator and part-time lecturer at the University of St. Andrews' Natural History Department. In October 1901, Punnett was back at Cambridge when he was elected to a Fellowship at Gonville and Caius College, working in zoology, primarily the study of worms, specifically nemerteans. It was during this time that he and William Bateson began a research collaboration, which lasted several years. When Punnett was an undergraduate, Gregor Mendel's work on inheritance was largely unknown and unappreciated by scientists. However, in 1900, Mendel's work was rediscovered by Carl Correns, Erich Tschermak von Seysenegg, and Hugo de Vries. William Bateson became a proponent of Mendelian genetics, and had Mendel's work translated into English and published as a chapter in Mendel's Principles of Heredity: A Defence. It was with Bateson that Reginald Punnett helped established the new science of genetics at Cambridge. He, Bateson and Saunders co-discovered genetic linkage through experiments with chickens and sweet peas.

Punnett's little book — Mendelism — is the first edition of the first genetics textbook ever written. It was published just five years after Mendel's work was rediscovered.

Cambridge: Bowes and Bowes

PDF image facsimile file: 1,832,735 bytes - 93 pages - several figures

Reginald Punnett was born in 1875 in the town of Tonbridge in Kent, England. Attending Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, Punnett earned a bachelor's degree in zoology in 1898 and a master's degree in 1901. Between these degrees he worked as a demonstrator and part-time lecturer at the University of St. Andrews' Natural History Department. In October 1901, Punnett was back at Cambridge when he was elected to a Fellowship at Gonville and Caius College, working in zoology, primarily the study of worms, specifically nemerteans. It was during this time that he and William Bateson began a research collaboration, which lasted several years. When Punnett was an undergraduate, Gregor Mendel's work on inheritance was largely unknown and unappreciated by scientists. However, in 1900, Mendel's work was rediscovered by Carl Correns, Erich Tschermak von Seysenegg, and Hugo de Vries. William Bateson became a proponent of Mendelian genetics, and had Mendel's work translated into English and published as a chapter in Mendel's Principles of Heredity: A Defence. It was with Bateson that Reginald Punnett helped established the new science of genetics at Cambridge. He, Bateson and Saunders co-discovered genetic linkage through experiments with chickens and sweet peas.

This second edition of Punnett's text on Mendelism came out just two years after the first edition. In this new edition, Punnett Squares appeared for the first time. Also, the author included an index (that could fit on a single page with room left over).

First published in 1965, it was brought back into print in 2001 by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press and the Electronic Scholarly Publishing project.

This is a full-text PDF typeset version of the entire 167-page original book.

Between 1910 and 1915, the modern chromosomal theory of heredity was established, largely through work done in the laboratory of Thomas H. Morgan at Columbia University. This book, by one of Morgan's students, presents the history of early genetics and captures the excitement as a new discipline was being born.

Sturtevant himself made major contributions to genetics, including the development of the world's first genetic map in 1913.

London: John Murray

This is a PDF image facsimile version of the entire 596-page original first edition.

This book is one of the first textbook treatments of heredity after the rediscovery of Mendel's work. Thomson provides his analysis in the context of the understanding of inheritance in the pre-Mendelian late nineteenth century. Chapter 11, History of Theories of Heredity and Inheritance summarizes many of the nineteenth-century theories of heredity.

In his bibliography, Thomson cites many nineteenth-century works. He also provides a subject-index to the bibliography, making this collection of citations especially valuable.

PDF typeset file: 557,634 bytes - 104 pages - no figures

Is there a more classic piece of humor than this? Besides it is in keeping with the biological orientation of this site, since it offers an alternative to evolution in explaining adaptation: "It is demonstrable," Pangloss said, "that things cannot be otherwise than as they are; for as all things have been created for some end, they must necessarily be created for the best end. Observe, for instance, the nose is formed for spectacles, therefore we wear spectacles. The legs are visibly designed for stockings, accordingly we wear stockings."

In any event, the book is a delightful read and provides both an antidote to excessive optimism and a basis for ultimate hope. "Excellently observed," answered Candide, "but let us cultivate out garden."

Chicago: The Open Court Publishing Co.

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 270-page original book

This classic work, first published in German in 1889, presents De Vries's theory of the pangen, a morphological structure carrying hereditary material. The name "gene," later coined by Johannsen, was derived from de Vries's pangen.

Hugo De Vries is often now remembered, along with Correns and von Tschermak, primarily for their role in the rediscovery of Mendel in 1900. Of the three, however, De Vries was by far the most established scientist. He was one of the most well-known botanists in Europe and had already been developing his own theoretical model of heredity - intracellular pangenesis.

Intracellular pangenesis was based on Darwins's concept of pangenesis as presented in chapter 27 of his massive, two-volume The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication. De Vries view, however, has a more modern feel than Darwin's, as De Vries thought about the inheritance of individual characters (as did Mendel), not just about more general overall species characteristics. De Vries called his units of inheritance pangens and later he came to believe that a pangen for a particular trait was the same, no matter in which species it occurred. This is an interesting anticipation of what would later be seen as genetic homology.

Oxford at the Clarendon Press

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 700-plus pages of the original volumes.

August Weismann was one of the most influential biologists of the late nineteenth century. In Essays Upon Heredity he presents a series of essays giving his thoughts on the mechanisms of heredity. Two of the essays offer specific refutation of the idea that acquired characters can be inherited.

New York: Charles Scribner's Sons

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 477-page original book.

August Weismann was one of the most influential biologists of the late nineteenth century. In The Germ-Plasm he lays out a new theory of heredity, one based on the continuity of the germ-plasm (the gametes and the cells that give rise to the gametes) as opposed to the finite existence of the soma (the cells of the body).

Weismann introduces his book modestly:

Any attempt at the present time to work out a theory of heredity in detail may appear to many premature, and almost presumptuous: I confess there have been times when it has seemed so even to myself. I could not, however, resist the temptation to endeavour to penetrate the mystery of this most marvellous and complex chapter of life as far as my own ability and the present state of our knowledge permitted.

A key point in his theory is that it makes impossible the inheritance of acquired characteristics, and thus deals a death blow to Lamarckism, as well as to Darwin's pangenesis:

What first struck me when I began seriously to consider the problem of heredity, some ten years ago, was the necessity for assuming the existence of a special organised and living hereditary substance, which in all multicellular organisms, unlike the substance composing the perishable body of the individual, is transmitted from generation to generation. This is the theory of the continuity of the germ-plasm. My conclusions led me to doubt the usually accepted view of the transmission of variations acquired by the body (soma); and further research, combined with experiments, tended more and more to strengthen my conviction that in point of fact no such transmission occurs.

The Cell in Development and Inheritance, 2nd Edition

New York: The Macmillan Company

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 490-page original book.

Edmund B. Wilson was the leading cytologist of his time and The Cell in Development and Inheritance was the definitive text on cytology from 1896 into the 1930's. A modern reader will be surprised to see how many of the illustrations in the book seem familiar – versions of many of them still appear in textbooks of introductory biology.

The last chapter in the book is entitled "Theories of Inheritance and Development:, and it begins:

Every discussion of inheritance and development must take as its point of departure the fact that the germ is a single cell similar in its essential nature to any one of the tissue-cells of which the body is composed. That a cell can carry with it the sum total of the heritage of the species, that it can in the course of a few days or weeks give rise to a mollusk or a man, is the greatest marvel of biological science. In attempting to analyze the problems that it involves, we must from the outset hold fast to the fact, on which Huxley insisted, that the wonderful formative energy of the germ is not impressed upon it from without, but is inherent in the egg as a heritage from the parental life of which it was originally a part. The development of the embryo is nothing new. It involves no breach of continuity, and is but a continuation of the vital processes going on in the parental body. What gives development its marvelous character is the rapidity with which it proceeds and the diversity of the results attained in a span so brief.

But when we have grasped this cardinal fact, we have but focussed our instruments for a study of the real problem. How do the adult characteristics lie latent in the germ-cell; and how do they become patent as development proceeds? This is the final question that looms in the background of every investigation of the cell. In approaching it we may well make a frank confession of ignorance; for in spite of all that the microscope has revealed, we have not yet penetrated the mystery, and inheritance and development still remain in their fundamental aspects as great a riddle as they were to the Greeks. What we have gained is a tolerably precise acquaintance with the external aspects of development. The gross errors of the early preformationists have been dispelled.' We know that the germ-cell contains no predelineated embryo; that development is manifested, on the one hand, by the cleavage of the egg, on the other hand, by a process of differentiation, through which the products of cleavage gradually assume diverse forms and functions, and so accomplish a physiological division of labour. We can clearly recognize the fact that these processes fall in the same category as those that take place in the tissue-cells; for the cleavage of the ovum is a form of mitotic cell-division, while, as many eminent naturalists have perceived, differentiation is nearly related to growth and has its root in the phenomena of nutrition and metabolism. The real problem of development is the orderly sequence and correlation of these phenomena toward a typical result. We cannot escape the conclusion that this is the outcome of the organization of the germ-cells; but the nature of that which, for lack of a better term, we call "organization," is and doubtless long will remain almost wholly in the dark.

First published in 1965, it was brought back into print in 2001 by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press and the Electronic Scholarly Publishing project.

This is a full-text PDF typeset version of the entire 167-page original book.

Between 1910 and 1915, the modern chromosomal theory of heredity was established, largely through work done in the laboratory of Thomas H. Morgan at Columbia University. This book, by one of Morgan's students, presents the history of early genetics and captures the excitement as a new discipline was being born.

Sturtevant himself made major contributions to genetics, including the development of the world's first genetic map in 1913.

London: J. M. Dent & Sons.

This is an image facsimile version of the entire 48-page original first edition.

This short book was based on a lecture given by Drinkwater as one of a series known as "Science Lectures for the People." The book provides insights into the general perception (as opposed to scholarly view) of genetics very early after the field had begun.

The book also contains some nice portraits of Mendel, Bateson, and Punnett.

An Essay on the Principle of Population.

PDF typeset file: 948,754 bytes - 134 pages - no figures

This book was first published anonymously in 1798, but the author was soon identified as Thomas Robert Malthus. The book predicted a grim future, as population would increase geometrically, doubling every 25 years, but food production would only grow arithmetically, which would result in famine and starvation, unless births were controlled. While it was not the first book on population, it was revised for over 28 years and has been acknowledged as the most influential work of its era. Malthus's book fuelled debate about the size of the population in the Kingdom of Great Britain and contributed to the passing of the Census Act 1800. This Act enabled the holding of a national census in England, Wales and Scotland, starting in 1801 and continuing every ten years to the present. The book's 6th edition (1826) was independently cited as a key influence by both Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace in developing the theory of natural selection.

rb> This book had a significant influence on Darwin as he looked for mechanisms that might explain evolutionary change. The influence shows, with Chapter Three of Darwin's Origin of Species entitled "Struggle for Existence".

PDF typeset file: 557,634 bytes - 104 pages - no figures

Is there a more classic piece of humor than this? Besides it is in keeping with the biological orientation of this site, since it offers an alternative to evolution in explaining adaptation: "It is demonstrable," Pangloss said, "that things cannot be otherwise than as they are; for as all things have been created for some end, they must necessarily be created for the best end. Observe, for instance, the nose is formed for spectacles, therefore we wear spectacles. The legs are visibly designed for stockings, accordingly we wear stockings."

In any event, the book is a delightful read and provides both an antidote to excessive optimism and a basis for ultimate hope. "Excellently observed," answered Candide, "but let us cultivate out garden."

Oxford at the Clarendon Press

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 700-plus pages of the original volumes.

August Weismann was one of the most influential biologists of the late nineteenth century. In Essays Upon Heredity he presents a series of essays giving his thoughts on the mechanisms of heredity. Two of the essays offer specific refutation of the idea that acquired characters can be inherited.

Facts and Arguments for Darwin.

London: John Murray, Albemarle Street

Johann Friedrich Theodor Müller (March 31, 1821 – May 21, 1897), always known as Fritz, was a German biologist and physician who emigrated to southern Brazil, where he lived in and near the German community of Blumenau, Santa Catarina. There he studied the natural history of the Atlantic forest south of São Paulo, and was an early advocate of Darwinism. He lived in Brazil for the rest of his life. Müllerian mimicry is named after him.

Müller became a strong supporter of Darwin. He wrote Für Darwin in 1864, arguing that Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection was correct, and that Brazilian crustaceans and their larvae could be affected by adaptations at any growth stage. This was translated into English by W.S. Dallas as Facts and Arguments for Darwin in 1869 (Darwin sponsored the translation and publication). If Müller had a weakness it was that his writing was much less readable than that of Darwin or Wallace; both the German and English editions are hard reading indeed, which has limited the appreciation of this significant book.

Heredity in Relation to Evolution and Animal Breeding.

New York: D. Appleton and Company

This is an image facsimile version of the entire 184-page original edition.

Heredity in the Light of Recent Research.

Cambridge: University Press

This is an image facsimile version of the entire 144-page original first edition.

London: John Murray

This is a PDF image facsimile version of the entire 596-page original first edition.

This book is one of the first textbook treatments of heredity after the rediscovery of Mendel's work. Thomson provides his analysis in the context of the understanding of inheritance in the pre-Mendelian late nineteenth century. Chapter 11, History of Theories of Heredity and Inheritance summarizes many of the nineteenth-century theories of heredity.

In his bibliography, Thomson cites many nineteenth-century works. He also provides a subject-index to the bibliography, making this collection of citations especially valuable.

Inborn Errors of Metabolism, Second Edition.

London: Henry Frowde and Hodder & Stoughton

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 216-page original book.

Less than two years after the rediscovery of Mendelism and just a few years after the word biochemistry was first coined, Garrod reported on alkaptonuria in humans and came to the conclusion that it was inherited as a Mendelian recessive and that the occurrence of mutations (sports in the word of the time) in metabolic function should be no more surprising than inherited variations in morphology.

In 1908, he summarized his thinking about "inborn errors of metabolism" (his term for what we would now think of as mutations in genes affecting metabolic function) in a book. An image facsimile of the second edition (1923) of that book is presented here.

Like Mendel's work, Garrod's insights were so far ahead of their time that his entire work on metabolic mutations was largely neglected, until later efforts to elucidate the physiological functioning of genes led to the Nobel-prize-winning one-gene, one-enzyme hypothesis.

Chicago: The Open Court Publishing Co.

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 270-page original book

This classic work, first published in German in 1889, presents De Vries's theory of the pangen, a morphological structure carrying hereditary material. The name "gene," later coined by Johannsen, was derived from de Vries's pangen.

Hugo De Vries is often now remembered, along with Correns and von Tschermak, primarily for their role in the rediscovery of Mendel in 1900. Of the three, however, De Vries was by far the most established scientist. He was one of the most well-known botanists in Europe and had already been developing his own theoretical model of heredity - intracellular pangenesis.

Intracellular pangenesis was based on Darwins's concept of pangenesis as presented in chapter 27 of his massive, two-volume The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication. De Vries view, however, has a more modern feel than Darwin's, as De Vries thought about the inheritance of individual characters (as did Mendel), not just about more general overall species characteristics. De Vries called his units of inheritance pangens and later he came to believe that a pangen for a particular trait was the same, no matter in which species it occurred. This is an interesting anticipation of what would later be seen as genetic homology.

Materials for the Study of Variation.

London: Macmillan and Company.

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 598-page original first edition.

William Bateson was the first English-speaking scientist to recognize the significance of Mendel's work. Before the rediscovery of Mendel's work in 1900, Bateson had been active in studying morphology, with a special interest in discontinuous variation as it might apply to the origin of species.

In this book Bateson summarizes his observations on discontinuous variation. His concern for this kind of variation probably contributed greatly to the quickness with which he grasped the significance of Mendel's work.

NOTE: This is an electronic FACSIMILE of the original work. The PDF files contain images of the original pages. The files are large and will download slowly. It is probably best to download the files to disk for later viewing and printing. When printed, these files give output equivalent to good quality Xerox copies of the original.

Mendel's Principles of Heredity: A Defence.

London: Cambridge University Press.

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 212-page original first edition.

William Bateson was the first English-speaking scientist to recognize the significance of Mendel's work. In an 1899 paper, he had anticipated the sort of experimental design that Mendel used, and in 1900, shortly after Mendel's rediscovery, he published another paper in which he summarized Mendel's work in English, declaring it to be "a new principle of the highest importance."

In the present work, Bateson offers a book-length presentation of Mendel's approach to genetic research, including the first English translation of both Mendel's work on peas and his later work on Hieracium. The book is subtitled A Defence because the Mendelian approach to genetics was initially strongly resisted by the biometrician school, which based their thinking on Galton's ancestral law of heredity.

NOTE: This is an electronic FACSIMILE of the original work. The PDF files contain images of the original pages. The files are large and will download slowly. It is probably best to download the files to disk for later viewing and printing. When printed, these files give output equivalent to good quality Xerox copies of the original.

Cambridge: Bowes and Bowes

PDF image facsimile file: 1,382,040 bytes - 71 pages - several figures

Reginald Punnett was born in 1875 in the town of Tonbridge in Kent, England. Attending Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, Punnett earned a bachelor's degree in zoology in 1898 and a master's degree in 1901. Between these degrees he worked as a demonstrator and part-time lecturer at the University of St. Andrews' Natural History Department. In October 1901, Punnett was back at Cambridge when he was elected to a Fellowship at Gonville and Caius College, working in zoology, primarily the study of worms, specifically nemerteans. It was during this time that he and William Bateson began a research collaboration, which lasted several years. When Punnett was an undergraduate, Gregor Mendel's work on inheritance was largely unknown and unappreciated by scientists. However, in 1900, Mendel's work was rediscovered by Carl Correns, Erich Tschermak von Seysenegg, and Hugo de Vries. William Bateson became a proponent of Mendelian genetics, and had Mendel's work translated into English and published as a chapter in Mendel's Principles of Heredity: A Defence. It was with Bateson that Reginald Punnett helped established the new science of genetics at Cambridge. He, Bateson and Saunders co-discovered genetic linkage through experiments with chickens and sweet peas.

Punnett's little book — Mendelism — is the first edition of the first genetics textbook ever written. It was published just five years after Mendel's work was rediscovered.

Cambridge: Bowes and Bowes

PDF image facsimile file: 1,832,735 bytes - 93 pages - several figures

Reginald Punnett was born in 1875 in the town of Tonbridge in Kent, England. Attending Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, Punnett earned a bachelor's degree in zoology in 1898 and a master's degree in 1901. Between these degrees he worked as a demonstrator and part-time lecturer at the University of St. Andrews' Natural History Department. In October 1901, Punnett was back at Cambridge when he was elected to a Fellowship at Gonville and Caius College, working in zoology, primarily the study of worms, specifically nemerteans. It was during this time that he and William Bateson began a research collaboration, which lasted several years. When Punnett was an undergraduate, Gregor Mendel's work on inheritance was largely unknown and unappreciated by scientists. However, in 1900, Mendel's work was rediscovered by Carl Correns, Erich Tschermak von Seysenegg, and Hugo de Vries. William Bateson became a proponent of Mendelian genetics, and had Mendel's work translated into English and published as a chapter in Mendel's Principles of Heredity: A Defence. It was with Bateson that Reginald Punnett helped established the new science of genetics at Cambridge. He, Bateson and Saunders co-discovered genetic linkage through experiments with chickens and sweet peas.

This second edition of Punnett's text on Mendelism came out just two years after the first edition. In this new edition, Punnett Squares appeared for the first time. Also, the author included an index (that could fit on a single page with room left over).

London: Macmillan

This is an image facsimile version of the entire 260-page original first edition.

London: Macmillan

This is an image facsimile version of the entire 260-page original first edition.

This is a full-text PDF version of the entire book.

Aristotle’s On the Generation of Animals (in Latin, De Generatione Animalium) was produced in the latter part of the fourth century B.C., exact date unknown. This book is the second recorded work on embryology as a subject of philosophy, being preceded by contributions in the Hippocratic corpus by about a century. It was, however, the first work to provide a comprehensive theory of how generation works and an exhaustive explanation of how reproduction works in a variety of different animals. As such, De Generatione was the first scientific work on embryology. Its influence on embryologists, naturalists, and philosophers in later years was profound. A brief overview of the general theory expounded in De Generatione requires an explanation of Aristotle’s philosophy. The Aristotelian approach to philosophy is teleological, and involves analyzing the purpose of things, or the cause for their existence. These causes are split into four different types: final cause, formal cause, material cause, and efficient cause. The final cause is what a thing exists for, or its ultimate purpose. The formal cause is the definition of a thing’s essence or existence, and Aristotle states that in generation, the formal cause and the final cause are similar to each other, and can be thought of as the goal of creating a new individual of the species. The material cause is the stuff a thing is made of, which in Aristotle’s theory is the female menstrual blood. The efficient cause is the “mover” or what causes the thing’s existence, and for reproduction Aristotle designates the male semen as the efficient cause. Thus, while the mother’s body contains all the material necessary for creating her offspring, she requires the father’s semen to start and guide the process.

London: John Murray, Albemarle Street.

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 502-page original first edition.

This is the book that changed the world and defined modern biology. By making mechanisms of heritable variation central to the biggest issue in all of biology, Darwin initiated the genetics revolution.

This is a full-text PDF version of the entire book.

Any collection of critical works in the history of biology must include works by Aristotle, as Aristotle was, essentially, the world's first biologist (if biologist is defined as one who conducts a scientific study of life). Although some earlier writers (e.g., Hippocrates) touched upon the human body and its health, no prior writer attempted a general consideration of living things. Aristotle held the study living things, especially animals, to be a critical foundation for the understanding of nature. No similarly broad attempt to understand biology occurred until the 16th century.

Here, in On the Parts of Animals, Aristotle provides a study in animal anatomy and physiology; it aims to provide a scientific understanding of the parts (organs, tissues, fluids, etc.) of animals.

Principles of Geology, Vols 1-3.

London: John Murray

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire three volumes.

These three volumes transformed the way people thought about the history of the earth. To understand Darwin's thinking, one must be familiar with Lyell's view of geology.

Proceedings of the Sixth International Congress of Genetics, Vol. I.

Austin, Texas: Genetics Society of America

This is an image facsimile version of the entire 396-page original edition.

The Proceedings of the Sixth International Congress of Genetics, held in 1932, offers a glimpse into classical genetics at the height of its power and influence. Thomas Morgan, who had just received the first Nobel Prize ever awarded in genetics, served as president of the congress.

The participants list reads like a who's who of classical genetics: The three rediscovers of Mendel — Correns, de Vries, and von Tschermak — all attended the meeting. Morgan, Sturtevant, and Muller gave talks. Population genetics and the relationship of genetics to evolution was discussed by R. A. Fisher, J. B. S. Haldane, and Sewall Wright.

NOTE: According to the Treasurer's Report, the total cost of the meeting was $17,583.58. Correcting for the effects of inflation, that would be $323,442.89 in 2018.

The Cell in Development and Inheritance, 2nd Edition

New York: The Macmillan Company

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 490-page original book.

Edmund B. Wilson was the leading cytologist of his time and The Cell in Development and Inheritance was the definitive text on cytology from 1896 into the 1930's. A modern reader will be surprised to see how many of the illustrations in the book seem familiar – versions of many of them still appear in textbooks of introductory biology.

The last chapter in the book is entitled "Theories of Inheritance and Development:, and it begins:

Every discussion of inheritance and development must take as its point of departure the fact that the germ is a single cell similar in its essential nature to any one of the tissue-cells of which the body is composed. That a cell can carry with it the sum total of the heritage of the species, that it can in the course of a few days or weeks give rise to a mollusk or a man, is the greatest marvel of biological science. In attempting to analyze the problems that it involves, we must from the outset hold fast to the fact, on which Huxley insisted, that the wonderful formative energy of the germ is not impressed upon it from without, but is inherent in the egg as a heritage from the parental life of which it was originally a part. The development of the embryo is nothing new. It involves no breach of continuity, and is but a continuation of the vital processes going on in the parental body. What gives development its marvelous character is the rapidity with which it proceeds and the diversity of the results attained in a span so brief.

But when we have grasped this cardinal fact, we have but focussed our instruments for a study of the real problem. How do the adult characteristics lie latent in the germ-cell; and how do they become patent as development proceeds? This is the final question that looms in the background of every investigation of the cell. In approaching it we may well make a frank confession of ignorance; for in spite of all that the microscope has revealed, we have not yet penetrated the mystery, and inheritance and development still remain in their fundamental aspects as great a riddle as they were to the Greeks. What we have gained is a tolerably precise acquaintance with the external aspects of development. The gross errors of the early preformationists have been dispelled.' We know that the germ-cell contains no predelineated embryo; that development is manifested, on the one hand, by the cleavage of the egg, on the other hand, by a process of differentiation, through which the products of cleavage gradually assume diverse forms and functions, and so accomplish a physiological division of labour. We can clearly recognize the fact that these processes fall in the same category as those that take place in the tissue-cells; for the cleavage of the ovum is a form of mitotic cell-division, while, as many eminent naturalists have perceived, differentiation is nearly related to growth and has its root in the phenomena of nutrition and metabolism. The real problem of development is the orderly sequence and correlation of these phenomena toward a typical result. We cannot escape the conclusion that this is the outcome of the organization of the germ-cells; but the nature of that which, for lack of a better term, we call "organization," is and doubtless long will remain almost wholly in the dark.

The Development of the Frog's Egg: An Introduction to Experimental Embryology.

New York: The Macmillan Company

PDF image facsimile file: 46,153,994 bytes - 204 pages - several figures

Thomas Hunt Morgan is best known for his work in genetics, for which he received the Nobel Prize in 1933. Morgan's first research interest, however, was in embryology. This short book on frog development is his first book.

From the Preface: The development of the frog's egg was first made known through the studies of Swammerdam, Spallanzani, Rusconi, and von Baer. Their work laid the basis for all later research. More recently the experiments of Pfluger and of Roux on this egg have turned the attention of embryologists to the study of development from an experimental standpoint. Owing to the ease with which the frog's egg can be obtained, and its tenacity of life in a confined space, as well as its suitability for experimental work, it is an admirable subject with which to begin the study of vertebrate development. In the following pages an attempt is made to bring together the most important results of studies of the development of the frog's egg. I have attempted to give a continuous account of the development, as far as that is possible, from the time when the egg is forming to the moment when the young tadpole issues from the jelly-membranes. Especial weight has been laid on the results of experimental work, in the belief that the evidence from this source is the most instructive for an interpretation of the development. The evidence from the study of the normal development has, however, not been neglected, and wherever it has been possible I have attempted to combine the results of experiment and of observation, with the hope of more fully elucidating the changes that take place. Occasionally departures have been made from the immediate subject in hand in order to consider the results of other work having a close bearing on the problem under discussion. I have done this in the hope of pointing out more definite conclusions than could be drawn from the evidence of the frog's egg alone.

This is a full-text PDF version of the entire book.

Francis Bacon was a contemporary of Queen Elizabeth I and Shakespeare. Bacon's philosophy emphasized the belief that people are the servants and interpreters of nature, that truth is not derived from authority, and that knowledge is the fruit of experience. Bacon is generally credited with having contributed to developing the logic of inductive reasoning, and thus to developing the scientific method.

Loren Eiseley (in The Man Who Saw Through Time) remarks that Bacon: "...more fully than any man of his time, entertained the idea of the universe as a problem to be solved, examined, meditated upon, rather than as an eternally fixed stage, upon which man walked."

Bacon saw himself as the inventor of a method which would kindle a light in nature - "a light that would eventually disclose and bring into sight all that is most hidden and secret in the universe." This method involved the collection of data, their judicious interpretation, the carrying out of experiments, thus to learn the secrets of nature by organized observation of its regularities.

New York: Charles Scribner's Sons

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 477-page original book.

August Weismann was one of the most influential biologists of the late nineteenth century. In The Germ-Plasm he lays out a new theory of heredity, one based on the continuity of the germ-plasm (the gametes and the cells that give rise to the gametes) as opposed to the finite existence of the soma (the cells of the body).

Weismann introduces his book modestly:

Any attempt at the present time to work out a theory of heredity in detail may appear to many premature, and almost presumptuous: I confess there have been times when it has seemed so even to myself. I could not, however, resist the temptation to endeavour to penetrate the mystery of this most marvellous and complex chapter of life as far as my own ability and the present state of our knowledge permitted.

A key point in his theory is that it makes impossible the inheritance of acquired characteristics, and thus deals a death blow to Lamarckism, as well as to Darwin's pangenesis:

What first struck me when I began seriously to consider the problem of heredity, some ten years ago, was the necessity for assuming the existence of a special organised and living hereditary substance, which in all multicellular organisms, unlike the substance composing the perishable body of the individual, is transmitted from generation to generation. This is the theory of the continuity of the germ-plasm. My conclusions led me to doubt the usually accepted view of the transmission of variations acquired by the body (soma); and further research, combined with experiments, tended more and more to strengthen my conviction that in point of fact no such transmission occurs.

This is a full-text PDF version of the entire book.

Any collection of critical works in the history of biology must include works by Aristotle. Here, in The History of Animals, Aristotle provides a discussion of the diversity of life, with considerable attention to reproduction and heredity.

In The History Aristotle frames his text by explaining that he is investigating the what (the existing facts about animals) prior to establishing the why (the causes of these characteristics). The book is thus an attempt to apply philosophy to part of the natural world. Throughout the work, Aristotle seeks to identify differences, both between individuals and between groups. A group is established when it is seen that all members have the same set of distinguishing features; for example, that all birds have feathers, wings, and beaks. This relationship between the birds and their features is recognized as a universal. The History of Animals contains many accurate eye-witness observations, in particular of the marine biology around the island of Lesbos, such as that the octopus had colour-changing abilities and a sperm-transferring tentacle, that the young of a dogfish grow inside their mother's body, or that the male of a river catfish guards the eggs after the female has left. Some of these were long considered fanciful before being rediscovered in the nineteenth century. Aristotle has been accused of making errors, but some are due to misinterpretation of his text, and others may have been based on genuine observation. He did however make somewhat uncritical use of evidence from other people, such as travellers and beekeepers. The History of Animals had a powerful influence on zoology for some two thousand years. It continued to be a primary source of knowledge until in the sixteenth century zoologists including Conrad Gessner, all influenced by Aristotle, wrote their own studies of the subject.

See also WIKIPEDIA: History of Animals

The Law of Heredity, Second Edition.

Baltimore and New York: John Murphy & Co., Publishers.

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 336-page original first edition.

It is often thought that, besides Mendel, little work on heredity occurred during the 19th Century. This is far from true. Darwin's Origin of Species placed the study of inherited variation at the center of biological thought. As this work by Brooks attests, considerable effort was made to understand heredity, especially as it related to natural selection.

Although the details of Brooks' analysis are now outdated, the book provides general insights into late-nineteenth Century thinking on heredity. Since Brooks was one of T. H. Morgan's instructors when Morgan was a student at Johns Hopkins, the book also provides insights into the specific instruction on heredity that was presented to the man who became the first recipient of a Nobel Prize for work on genetics.

NOTE: This is an electronic FACSIMILE of the original work. The PDF files contain images of the original pages. The files are large and will download slowly. It is probably best to download the files to disk for later viewing and printing. When printed, these files give output equivalent to good quality Xerox copies of the original.

The Mechanism of Crossing-over.

New York: The American Naturalist

This is an image facsimile version of the entire 86-page original edition.

Beginning 1910, T. H. Morgan and his students established the foundations of modern genetics by demonstrating that genes were real — not theoretical — entities.

This work is a collection of papers that represented the doctoral dissertation of one of those students - H. J. Muller.

The Mechanism of Mendelian Heredity.

New York: Henry Holt and Company

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 262-page original book.

This book, by T. H. Morgan and his students, is the first work to articulate a comprehensive, mechanistic model to explain Mendelian patterns of inheritance.

Although Mendelism had quickly been accepted as a good phenomenological explanation for the patterns seen in Mendelian crosses, until the work of Morgan's group, it was still possible to consider Mendelism to be a purely theoretical model of heredity. As Morgan's group first established the relationship of genes to chromosomes, then developed the first genetic map, and went on to describe a variety of interactions between chromosomes and Mendelian factors, the conclusions they offered became inescapable - genes are physical objects, carried on chromosomes in static locations.

Morgan's group made genes real and this book is the first full-length presentation of their findings. It revolutionized the study of heredity.

The Methods and Scope of Genetics.

London: Cambridge University Press.

This is a newly typeset full-text version of the entire 49-page original first edition.

This short book is a copy of the Inaugural Address, given by Bateson upon the creation of the Professorship of Biology at Cambridge. In his introduction, Bateson notes:

The Professorship of Biology was founded in 1908 for a period of five years partly by the generosity of an anonymous benefactor, and partly by the University of Cambridge. The object of the endowment was the promotion of inquiries into the physiology of Heredity and Variation, a study now spoken of as Genetics.

It is now recognized that the progress of such inquiries will chiefly be accomplished by the application of experimental methods, especially those which Mendel's discovery has suggested. The purpose of this inaugural lecture is to describe the outlook over this field of research in a manner intelligible to students of other parts of knowledge.

Here then is a view of how one of the very first practitioners of genetics conceived of the "Methods and Scope of Genetics".

The Physical Basis of Heredity.

Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 305-page original book.

In this book, T. H. Morgan (who would later receive the first Nobel Prize for genetics research) describes the model of heredity developed at Columbia by Morgan and his students.

The foundations of genetics were laid down by Mendel, and these were brought to the world's attention when his work was rediscovered by Correns, de Vries, and von Tschermak in 1900. But the real establishment of genetics as a real science, with a known physical basis, did not occur until the work outlined in this book became generally known.

To understand the true conceptual underpinnings of classical genetics, one must read the publications from "The Fly Room" at Columbia.

New York: Dix, Edwards, & Co.

This is a full-text newly typeset, PDF version of the entire book.

Included in this collection of short works by Herman Melville (author of Moby Dick) is "The Encantadas" — a description of the Galapagos Islands.

The Theory of the Gene, Revised and Enlarged Edition.

New Haven: Yale University Press

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 358-page original book.

This book, by T. H. Morgan, summarizes the state of knowledge on classical genetics in the mid 1920's.

Although Mendelism had quickly been accepted as a good phenomenological explanation for the patterns seen in Mendelian crosses, until the work of Morgan's group, it was still possible to consider Mendelism to be a purely theoretical model of heredity. As Morgan's group first established the relationship of genes to chromosomes, then developed the first genetic map, and went on to describe a variety of interactions between chromosomes and Mendelian factors, the conclusions they offered became inescapable – genes are physical objects, carried on chromosomes in static locations.

Less than 15 years after Morgan first started working with fruit flies, the foundations for a theory of the gene had been worked out – largely by Morgan and students working in his laboratory.

The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, Second Edition, Revised (two volumes).

New York: D. Appleton & Co.

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 473-page volume I and the entire 495-page volume II of the original work.

Although Darwin's theories regarding the origin of species through natural selection required that some mechanism of heredity exist, no such mechanism was known when the Origin was written. After the Origin appeared, Darwin turned his attention to the mechanism(s) of heredity, resulting in his subsequent two-volume The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication.

In volume I, Darwin summarized what was known about inheritance in a variety of domesticated species and concluded with a chapter, Inheritance, that begins his general summary of the mechanisms of inheritance. He continued this summary in volume II, which also offers Darwin's own theory of inheritance in Chapter XXVII, Provisional Hypothesis of Pangenesis.

The notion of pangenesis dominated late nineteenth-century thinking about inheritance. Although ultimately seen to be simply wrong, it was very influential and a familiarity with its tenets is essential for anyone wishing to understand the intellectual climate at the time Mendel was rediscovered in 1900.

NOTE: This is an electronic FACSIMILE of the original work. The PDF files contain images of the original pages. The files are large and will download slowly. It is probably best to download the files to disk for later viewing and printing. When printed, these files give output equivalent to good quality Xerox copies of the original.

The Voyage of the Beagle, Second Edition.

London: John Murray.

This is a full-text, newly typeset, PDF version of the entire book.

For five years, from 1831-1836, Charles Darwin served as the official naturalist aboard the HMS Beagle as it visited exotic locations around the world. During this voyage, Darwin first came to wonder about the mechanisms driving the origin of species. This book chronicles the voyage and documents his early thinking.

Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation.

London: John Churchill.

This is a full-text PDF image facsimile version of the entire 390-page original first edition.

In 1859, many had already begun to think deeply about the meaning and origin of creation. Fifteen years before the Origin, Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation appeared, published anonymously. In one sense, the book is hopelessly dated, and amateurish to boot. In another, the book is incredibly modern - an effort, in the author's own words, "to connect the natural sciences into a history of creation."

At one point, the author (revealed in the 12th edition to be Robert Chambers) uses the example of Charles Babbage's calculating engine (the first computer) to show how apparently miraculous changes might occur as the result of subtle changes in an underlying governing system.

NOTE: This is an electronic FACSIMILE of the original work. The PDF files contain images of the original pages. The files are large and will download slowly. It is probably best to download the files to disk for later viewing and printing. When printed, these files give output equivalent to good quality Xerox copies of the original.

This is a full-text PDF version of the entire book.

Aristotle’s On the Generation of Animals (in Latin, De Generatione Animalium) was produced in the latter part of the fourth century B.C., exact date unknown. This book is the second recorded work on embryology as a subject of philosophy, being preceded by contributions in the Hippocratic corpus by about a century. It was, however, the first work to provide a comprehensive theory of how generation works and an exhaustive explanation of how reproduction works in a variety of different animals. As such, De Generatione was the first scientific work on embryology. Its influence on embryologists, naturalists, and philosophers in later years was profound. A brief overview of the general theory expounded in De Generatione requires an explanation of Aristotle’s philosophy. The Aristotelian approach to philosophy is teleological, and involves analyzing the purpose of things, or the cause for their existence. These causes are split into four different types: final cause, formal cause, material cause, and efficient cause. The final cause is what a thing exists for, or its ultimate purpose. The formal cause is the definition of a thing’s essence or existence, and Aristotle states that in generation, the formal cause and the final cause are similar to each other, and can be thought of as the goal of creating a new individual of the species. The material cause is the stuff a thing is made of, which in Aristotle’s theory is the female menstrual blood. The efficient cause is the “mover” or what causes the thing’s existence, and for reproduction Aristotle designates the male semen as the efficient cause. Thus, while the mother’s body contains all the material necessary for creating her offspring, she requires the father’s semen to start and guide the process.

This is a full-text PDF version of the entire book.